HackerRank has a simple programming problem called Number Line Jumps that states:

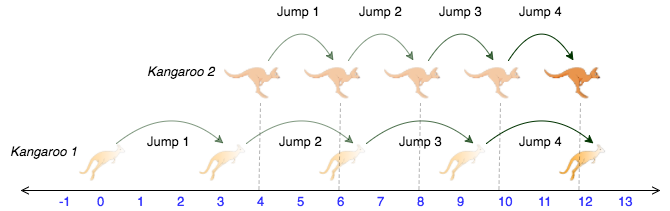

You are choreographing a circus show with various animals. For one act, you are given two kangaroos on a number line ready to jump in the positive direction (i.e, toward positive infinity).

- The first kangaroo starts at location and moves at a rate of meters per jump.

- The second kangaroo starts at location and moves at a rate of meters per jump.

You have to figure out a way to get both kangaroos at the same location at the same time as part of the show. If it is possible, return

YES, otherwise returnNO.

NOTE: Although not explicitly stated, it’s implied that the kangaroos always jump at the same time.

Iteration and its limits

With the constraints given of and and , the problem is very simple and can be easily solved with a brute force approach. As we know there will be no more than jumps, we can iteratively simulate the jumps of both kangaroos and check if they ever land on the same spot, returning YES if they do while otherwise returning NO. This approach gives us a time complexity of which should be acceptable when .

e.g.

from typing import Literal

def number_line_jumps(

x1: int,

v1: int,

x2: int,

v2: int

) -> Literal["YES", "NO"]:

if x1 == x2:

return "YES"

p1, p2 = x1, x2

for _ in range(10000):

p1 += v1

p2 += v2

if p1 == p2:

return "YES"

return "NO"However, if we remove the limit of from each constraint, we have difficulties. If the kangaroos never land on the same spot, we get an infinite loop! We can still solve this using iteration but must ensure that we only iterate while the kangaroos are getting closer to each other, and that we exit our loop if each iteration has the kangaroos getting further apart. Unfortunately, this has us keeping track of the distance between the kangaroos, complicating our solution quite a bit. For example, in Python, we might write something like the following:

from typing import Literal

def number_line_jumps(

x1: int,

v1: int,

x2: int,

v2: int

) -> Literal["YES", "NO"]:

# If the kangaroos start at the same location, then we can

# immediately return YES.

if x1 == x2:

return "YES"

# If the kangaroo furthest away is moving faster, the other

# will never catch up.

if x1 >= x2 and v1 >= v2:

return "NO"

if x2 >= x1 and v2 >= v1:

return "NO"

# Otherwise, we iterate until:

# (1) the kangaroos are at the same location,

# (2) or, exit the loop if they are diverging and the

# difference between them is increasing.

p1, p2 = x1, x2

prev_diff = float("inf")

while abs(p1 - p2) < prev_diff:

prev_diff = abs(p1 - p2)

p1 += v1

p2 += v2

if p1 == p2:

return "YES"

return "NO"I think it’s quite natural for a software engineer to reach for a solution like this. When all you have is iteration, everything looks like a loop.

But, there’s a much more elegant solution to this question that naturally follows from use of mathematical notation.

Notation

If we recall from the problem statement:

- The first kangaroo starts at location and moves at a rate of meters per jump.

- The second kangaroo starts at location and moves at a rate of meters per jump.

We can formulate the position of each kangaroo as a function of the number of jumps they’ve taken, . For example, the position of each kangaroo after jumps is given by:

These position functions are linear equations. We could plot them on a graph to see whether they intersect and if so where, or we could solve them algebraically by setting and solving for . Like so:

Synthesis

The equation produced (i.e. ) allows us to determine whether the kangaroos will ever land on the same spot, and, if so, how many jumps it will take.

This equation is almost directly applicable to solving this problem, apart from two issues that must be handled:

-

When the result is indeterminate (either a

NaNor a divide-by-zero error depending on your choice of programming language). This implies that when plotted on a graph, the slope of each line will run parallel to the other, never intersecting. In this situation, the kangaroos will never land on the same spot, unless they started at the same location. -

When is a non-integer, it implies that the kangaroos will be at the same position mid-jump but never land on the same spot.

After resolving these two issues, the finished solution looks like this:

from typing import Literal

def number_line_jumps(

x1: int,

v1: int,

x2: int,

v2: int

) -> Literal["YES", "NO"]:

# If the kangaroos start at the same location, then we can

# immediately return YES.

if x1 == x2:

return "YES"

# If the kangaroos are moving at the same speed, but started

# at different locations, they will never land on the same

# spot.

if v1 == v2:

return "NO"

# Finally, instead of iterating we can use the equation we

# derived above to determine whether j is an integer or not

# by using the modulo operator to check that the remainder

# of the division is zero.

#

# Put in another way, the difference between their starting

# positions must be divisible evenly by the difference in

# their speeds for them to meet. The reason for this is that

# the difference (v1 - v2) represents the incremental step size

# in the difference between the two starting positions. If it

# doesn't divide evenly, that means they will never land on the

# same spot.

if (x2 - x1) % (v1 - v2) == 0:

return "YES"

return "NO"This solution is not only much more elegant than the iterative solution, it’s also more efficient as it has a time complexity of instead of .

I think it’s very easy to get tunnel vision when programming and to not see mathematical relationships. For those of you that grew up in the UK, this is Key Stage 3 material that is covered prior to GCSE maths, yet it wasn’t my first instinct to reach for it.

Conclusion

The learning I took away from this was that even if you haven’t yet developed the right mindset to immediately discern mathematical solutions, writing things down using mathematical notation can be a very useful tool in your arsenal. It can make these relationships more apparent and help with pattern matching mathematical approaches to solving problems.