Recently, while working on a problem from the CSES Problem Set known as #1071: “Number Spiral”, I accidentally misread the problem description and instead of finding for a given , solved the inverse by finding for a given . This problem turned out to have an interesting solution based on simple mathematical reasoning and as I couldn’t find any other solutions for this variant online, I thought I’d share my solution here.

I’ve named this the “Inverse Number Spiral” problem and here is the problem description:

Problem

#: Inverse Number Spiral

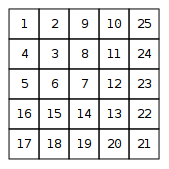

Time limit: 1.00 s Memory limit: 512 MBA number spiral is an infinite grid whose upper-left square has number 1. Here are the first five layers of the spiral:

Your task is to find out the row and column given a number .

Input

The first input line contains an integer : the number of tests.

After this, there are lines, each containing an integer .

Output

For each test, print the row and column .

Constraints

Example

Input:

3 8 1 15Output:

2 3 1 1 4 2

Analysis

My initial thought was that I could solve this problem by simply iterating over the spiral and checking if the current number is equal to the given number . I imagined a robot starting at position , moving like a snake—right, down, left and up—while adjusting the number of steps in each direction. However, understanding the sequence of steps proved to be quite challenging. The pattern appeared complex and difficult to comprehend, making it difficult to implement (e.g. right 1, down 1, left 1, down 1, right 2, up 2, right 1, down 3, left 3, down 1, right 4, up 4, and so on).

The time complexity of such an algorithm is . However, the number of tests is also an input parameter, which makes the overall time complexity . Given that there can be up to tests and up to input numbers, a brute-force approach could potentially require up to iterations which may cause the program to exceed the time limit.

Given these challenges, I decided to look to see whether I could find an alternative approach.

As I contemplated the spiral grid, I recognised a familiar pattern at the end of each layer of the spiral:

It was the sequence of square numbers (e.g. ). This observation sparked my curiosity and led me to wonder if I could leverage this pattern to my advantage.

I realised that the maximum value in each layer of the spiral was equal to the square of the layer number . For example, the maximum value in layer 3 was $3^2 = 9$, the maximum value in layer 4 was $4^2 = 16$, and so on. This meant that I could use the square root function to determine the layer number for a given value . Only the square numbers of a layer would directly produce the layer number when taking a square root, however all values in the layer including its minimum produce a decimal value greater than the previous layer number and therefore as long as we round up this value to the nearest integer (e.g. Math.ceil) our method produces the correct layer number.

function function layer(N: number): numberlayer(type N: numberN: number) {

return var Math: MathAn intrinsic object that provides basic mathematics functionality and constants.Math.Math.ceil(x: number): numberReturns the smallest integer greater than or equal to its numeric argument.ceil(var Math: MathAn intrinsic object that provides basic mathematics functionality and constants.Math.Math.sqrt(x: number): numberReturns the square root of a number.sqrt(type N: numberN));

}

const const L1: numberL1 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(1); // 1

const const L2: numberL2 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(2); // 2

const const L3: numberL3 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(3); // 2

const const L4: numberL4 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(4); // 2

const const L5: numberL5 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(5); // 3

const const L6: numberL6 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(6); // 3

const const L7: numberL7 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(7); // 3

const const L8: numberL8 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(8); // 3

const const L9: numberL9 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(9); // 3

const const L10: numberL10 = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(10); // 4Once I had a layer number , I was able to use this to determine the range of values for that layer, as for a given layer the maximum value is and the minimum value is (if you add one to the maximum value of the previous layer you get the minimum of the layer that follows it).

function function layerRange(L: number): readonly [number, number]layerRange(type L: numberL: number) {

const const start: numberstart = var Math: MathAn intrinsic object that provides basic mathematics functionality and constants.Math.Math.pow(x: number, y: number): numberReturns the value of a base expression taken to a specified power.pow(type L: numberL - 1, 2) + 1;

const const end: numberend = var Math: MathAn intrinsic object that provides basic mathematics functionality and constants.Math.Math.pow(x: number, y: number): numberReturns the value of a base expression taken to a specified power.pow(type L: numberL, 2);

return [const start: numberstart, const end: numberend] as type const = readonly [number, number]const;

}

const const R1: readonly [number, number]R1 = function layerRange(L: number): readonly [number, number]layerRange(1); // [1, 1]

const const R2: readonly [number, number]R2 = function layerRange(L: number): readonly [number, number]layerRange(2); // [2, 4]

const const R3: readonly [number, number]R3 = function layerRange(L: number): readonly [number, number]layerRange(3); // [5, 9]

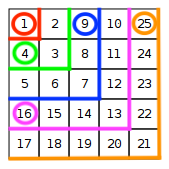

const const R4: readonly [number, number]R4 = function layerRange(L: number): readonly [number, number]layerRange(4); // [10, 16]The way I saw it at this point was that a layer range represented a sort of one-dimensional version of each layer of the spiral. In order to determine the coordinates for a given value , I would need to be able to determine the position of within this layer, and then be able to translate that position back into coordinates.

I found that I was able to get the position of within the one-dimensional layer range quite easily by subtracting the minimum value of the layer from . For example, the position of in layer 3 was $7 - 5 = 2$. However, in order to convert the one-dimensional position into two-dimensional coordinates within the grid, there were two further properties of the spiral that I needed to use to my advantage:

- The spiral goes in a clockwise direction in even layers and an anti-clockwise direction in odd layers.

- Depending on the position of in relation to the mid-point of the layer range and the direction of the spiral, the or coordinates are either set to the layer number or calculated. For example, the spiral travels anti-clockwise in the 5th layer and therefore when the position of within the layer range is less than or equal to its mid-point, the coordinate of is the layer number , however, when the position of within the layer range is greater than its mid-point, the coordinate of is the layer number . The inverse is true for even layers.

Solution

With all of this in mind, I was finally able to determine the coordinates for a given value , like so:

function function layer(N: number): numberlayer(type N: numberN: number) {

return var Math: MathAn intrinsic object that provides basic mathematics functionality and constants.Math.Math.ceil(x: number): numberReturns the smallest integer greater than or equal to its numeric argument.ceil(var Math: MathAn intrinsic object that provides basic mathematics functionality and constants.Math.Math.sqrt(x: number): numberReturns the square root of a number.sqrt(type N: numberN));

}

function function layerRange(L: number): readonly [number, number]layerRange(type L: numberL: number) {

const const start: numberstart = var Math: MathAn intrinsic object that provides basic mathematics functionality and constants.Math.Math.pow(x: number, y: number): numberReturns the value of a base expression taken to a specified power.pow(type L: numberL - 1, 2) + 1;

const const end: numberend = var Math: MathAn intrinsic object that provides basic mathematics functionality and constants.Math.Math.pow(x: number, y: number): numberReturns the value of a base expression taken to a specified power.pow(type L: numberL, 2);

return [const start: numberstart, const end: numberend] as type const = readonly [number, number]const;

}

function function direction(L: number, axis: "y" | "x"): 1 | -1direction(type L: numberL: number, axis: "y" | "x"axis: "y" | "x") {

switch (axis: "y" | "x"axis) {

case "y": {

// Determine the direction for the "y" axis based on the even/odd nature

// of the layer (L). If L is even, the direction is down (1); otherwise,

// it is up (-1).

return type L: numberL % 2 === 0 ? 1 : -1;

}

case "x": {

// Determine the direction for the "x" axis based on the even/odd nature

// of the layer (L). If L is even, the direction is left (-1); otherwise,

// it is right (1).

return type L: numberL % 2 === 0 ? -1 : 1;

}

default: {

throw new var Error: ErrorConstructor

new (message?: string, options?: ErrorOptions) => Error (+1 overload)

axis: neveraxis}`);

}

}

}

function function coord(N: number, axis: "y" | "x"): numbercoord(type N: numberN: number, axis: "y" | "x"axis: "y" | "x") {

const const L: numberL = function layer(N: number): numberlayer(type N: numberN);

const [const start: numberstart, const end: numberend] = function layerRange(L: number): readonly [number, number]layerRange(const L: numberL);

// The `sequenceIndex` is a zero-indexed "position" of `N` within the layer

// range.

const const sequenceIndex: numbersequenceIndex = type N: numberN - const start: numberstart;

// The `midIndex` is the zero-indexed mid-point of the layer range.

const const midIndex: numbermidIndex = (const end: numberend - const start: numberstart) / 2;

// Depending on the direction of the spiral and the axis, the coordinate

// can be either (1) the layer number `L`, (2) the position of `N` computed

// by starting from the beginning of the layer range, (3) the position of

// `N` computed by starting from the end of the layer range and counting

// backwards towards the center.

//

// The value of `D` might be somewhat difficult to grasp at first as it

// abstracts away the direction (clockwise/anti-clockwise) and the axis

// into a single value, that determines whether the coordinate is

// calculated by counting forwards towards the middle of the layer range

// or counting backwards from the end towards the middle of the layer

// range.

const const D: 1 | -1D = function direction(L: number, axis: "y" | "x"): 1 | -1direction(const L: numberL, axis: "y" | "x"axis);

switch (const D: 1 | -1D) {

// If the direction is down or right.

case 1: {

if (const sequenceIndex: numbersequenceIndex <= const midIndex: numbermidIndex) {

// For the first half of the sequence, the coordinate is simply the

// `sequenceindex` incremented by one to convert it from

// zero-indexed to one-indexed.

return 1 + const sequenceIndex: numbersequenceIndex;

}

// For the second half of the sequence, the coordinate is the layer `L`

// itself.

return const L: numberL;

}

// If the direction is up or left.

case -1: {

if (const sequenceIndex: numbersequenceIndex > const midIndex: numbermidIndex) {

// For the second half of the sequence, the coordinate is calculated

// by counting back from the maximum value of the outer layer `L`

// towards the center. We do this by subtracting the difference

// between the `sequenceindex` and the `midIndex` from the layer `L`.

return const L: numberL - (const sequenceIndex: numbersequenceIndex - const midIndex: numbermidIndex);

}

// For the first half of the sequence, the coordinate is the layer `L`

// itself.

return const L: numberL;

}

default: {

throw new var Error: ErrorConstructor

new (message?: string, options?: ErrorOptions) => Error (+1 overload)

function direction(L: number, axis: "y" | "x"): 1 | -1direction}`);

}

}

}

function function y(N: number): numbery(type N: numberN: number) {

return function coord(N: number, axis: "y" | "x"): numbercoord(type N: numberN, "y");

}

function function x(N: number): numberx(type N: numberN: number) {

return function coord(N: number, axis: "y" | "x"): numbercoord(type N: numberN, "x");

}

function function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(type N: numberN: number) {

return [function y(N: number): numbery(type N: numberN), function x(N: number): numberx(type N: numberN)] as type const = readonly [number, number]const;

}

const const F1: readonly [number, number]F1 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(1); // [1, 1]

const const F4: readonly [number, number]F4 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(4); // [2, 1]

const const F7: readonly [number, number]F7 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(7); // [3, 3]

const const F9: readonly [number, number]F9 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(9); // [1, 3]

const const F11: readonly [number, number]F11 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(11); // [2, 4]

const const F13: readonly [number, number]F13 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(13); // [4, 4]

const const F14: readonly [number, number]F14 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(14); // [4, 3]

const const F17: readonly [number, number]F17 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(17); // [5, 1]

const const F18: readonly [number, number]F18 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(18); // [5, 2]

const const F24: readonly [number, number]F24 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(24); // [2, 5]

const const F25: readonly [number, number]F25 = function f(N: number): readonly [number, number]f(25); // [1, 5]Conclusion

By identifying patterns in the number spiral and leveraging mathematical relationships, we were able to transform a seemingly complex problem into a solvable one. In the process, we developed an efficient algorithm that significantly reduced the time complexity compared to a brute-force approach.

Because we are able to calculate the coordinates for a given number using only constant-time mathematical operations, the time complexity of the solution is . When we execute f(N) for each test case in the input, the overall time complexity becomes , a substantial improvement over the brute-force approach which would have a time complexity of .

Although further optimizations, such as memoizing f(N) to minimize duplicate calculations, could still be made, the current solution is both efficient and elegant.

Now that you’ve seen our approach to solving this problem, we encourage you to try your hand at the original “Number Spiral” problem. Finally, if you’re looking for more challenges, the entire CSES Problem Set is an excellent resource to explore, offering a wide range of problems to hone your coding and problem-solving skills.